Address

WARISPURA HOUSE NUMBER 1074-B CHAMANZAR COLONY STREET NUMBER 1 FAISALABAD PAKISTAN

RESCUE US

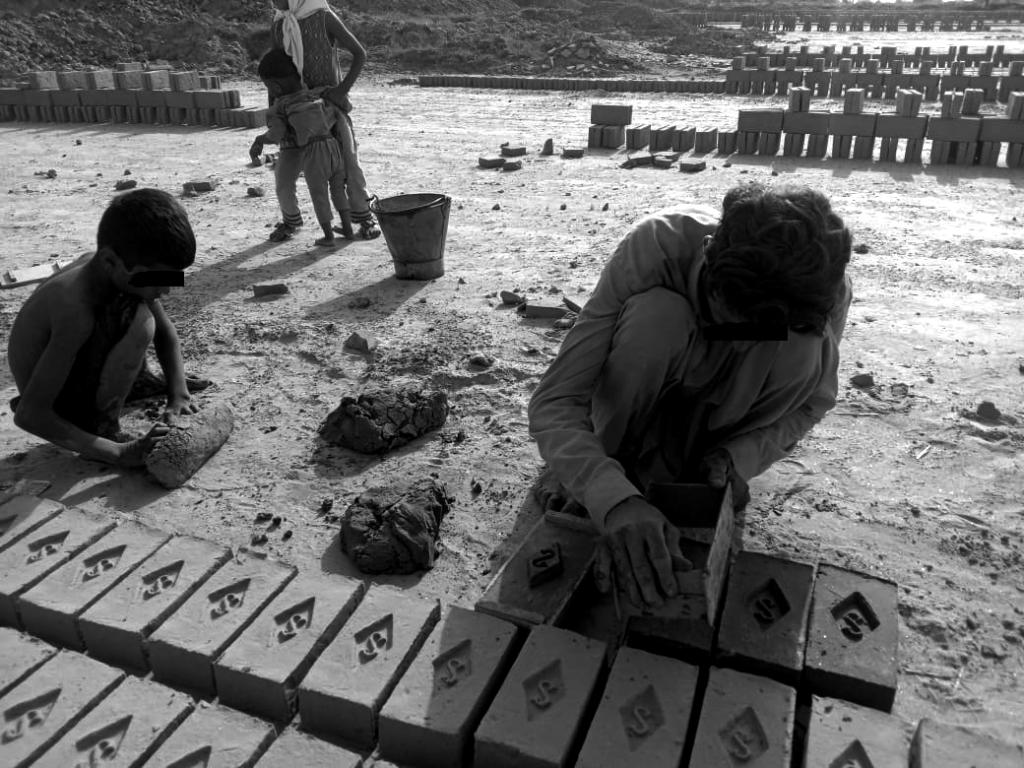

The money they owe keeps increasing, spiralling out of reach, thus keeping them and future generations in debt. Reasons for this can include high interest on the amount borrowed, low wages further cut due to corrupt officials, increasing and unlawful deductions, and forged entries into the books that the workers do not get to see

“The bricks that these workers make are used to make houses, hospitals, schools, universities and the parliament. But they never get to benefit from what they are making”

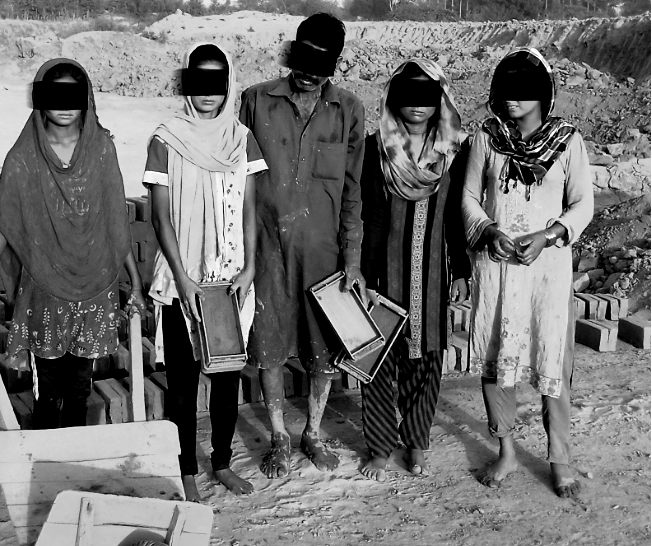

In Pakistan, it is illegal to employ someone who is under 16 years of age. But almost 70 percent of bonded labourers in Pakistan are children, who make up over one-third of the four million or so people working at brick kilns in Pakistan. Often, they work all day and are denied education.

There are cases where children inherit debts from parents and became bonded as individuals for a long time. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan reports a high mortality rate among children working at brick kilns. In addition, about one in 20 families living in brick kilns have children who have lost their eyesight.

Children are kept as hostages in the event of the parents leaving the kiln, even for a short period. The workers do not sign a contract when they are taken to a brick kiln. Most of them cannot read, so they have no way of finding out what is being added to their accounts.

Some of the workers who manage to flee or are freed are taken back to the kiln by the owners by force. With no inspection of these sites, they have no protection and often end up in harsher conditions upon their return, with a hefty fine added to their existing debt.

There have also been cases where an escaped worker’s daughter has been forcibly married off – or sold – as “payment” for the days he had been in hiding for. As debts are manipulated upwards year after year, an overall sense of helplessness overcomes most labourers, notes Siddharth Kara in his book, Bonded Labor

“While some may have family members forcibly sold to repay their debts, others give up and commit suicide,” wrote Kara, before adding that there has been an alarming number of workers selling kidneys to repay part or all of their debts.

The needs of our persecuted brothers and sisters are multiplying. On top of the threats, abuse, and ostracism they already experience for their faith, these believers are struggling to survive under the constant threat to their life.

Emancipation of Women and Children in bonded labour Pakistan

WHAT IS BONDED LABOR?

Bonded labor is the most extensive form of slavery in the world today. There were approximately eighteen to 20.5 million bonded laborers in the world at the end of 2011, roughly 84 percent to 88 percent of whom were in South Asia.

This means that approximately half of the slaves in the world are bonded laborers in South Asia and that approximately 1.1 percent of the total population of South Asia is ensnared in bonded labor. Bonded labor is at once the most ancient and most contemporary face of human servitude. While it spans the breadth and depth of all manner of servile labor going back millennia, the products of present-day bonded labor touch almost every aspect of the global economy, including frozen shrimp and fish, tea, coffee, rice, wheat, diamonds, gems, cubic zirconia, glassware, brassware, carpets, limestone, marble, slate, salt, matches, cigarettes, bidis (Indian cigarettes), apparel, fireworks, knives, sporting goods, and many other products. Virtually everyone’s life, everywhere in the world, is touched by bonded labor in South Asia.

For this reason alone, it is incumbent that we understand, confront, and eliminate this evil. In its most essential form, bonded labor involves the exploitative interlinking of labor and credit agreements between parties. On one side of the agreement, a party possessing an abundance of assets and capital provides credit to the other party, who, because he lacks almost any assets or capital, pledges his labor to work off the loan. Given the severe power imbalances between the parties, the laborer is often severely exploited. Bonded labor occurs when the exploitation ascends to the level of slavelike abuse. In these cases, once the capital is borrowed, numerous tactics are used by the lender to extract the slave labor. The borrower is often coerced to work at paltry wage levels to repay the debt. Exorbitant interest rates are charged (from 20 per cent to more than 30 percent per month), and money lent for future medicine, clothes, or basic subsistence is added to the debt. In most cases of bonded labor, up to half or more of the day’s wage is deducted for debt repayment, and further deductions are often made as penalties for breaking rules or poor work performance.

The laborer uses what paltry income remains to buy food and supplies from the lender, at heavily inflated prices. The bonded laborers rarely have enough money to meet their subsistence needs, so they are forced to borrow more money to survive. Any illness or injury spells disaster. Incremental money must be borrowed not only for medicine but also because the injured individuals cannot work, and thus the family is not earning enough income for daily consumption, requiring more loans and deeper indebtedness.

Sometimes the debts last a few years, and sometimes the debts are passed on to future generations if the original borrower perishes without having repaid the debt (according to the lender). In my experience, this generational debt bondage is a waning phenomenon, though it does still occur throughout South Asia. More often, the terms of debt bondage agreements last a few years or even just a season. However, because of a severe lack of any reasonable alternative income or credit source, the laborer must return time and again to the lender, which recommences his exploitation in an ongoing cycle of debt bondage.

The term “bonded labor” is typically used interchangeably with “debt bondage,” though the former term has been more often used to describe the distinctive mode of debt bondage that has persisted in South Asia across centuries. Beyond South Asia, there have been numerous variations on tied labor-credit economic arrangements spanning centuries of human history, commencing with the early agricultural economies.

Perhaps the most important feature shared by bonded laborers in South Asia is extreme poverty. Each and every bonded laborer I met lived in abject poverty without a reliable means of securing sufficient subsistence income. Almost 1.2 billion people in South Asia live on incomes of less than $2 per day.

The second feature shared by almost all bonded laborers in South Asia is that they belong to a minority ethnic group or caste. The issue of caste will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter, but, in summary, it is crucial to understand that there remains a stratum of human beings in South Asia who are deemed exploitable and expendable by society at large. Be they dalits or tharu, adivasi or janjati, minority ethnicities and castes in South Asia are the victims of a social system that at best exiles them and at worst disdains them.

Almost all bonded laborers lack access to formal credit markets. This is primarily because, other than their labor, they typically have no collateral to offer against a loan. Coupled with an inability to earn sufficient income to save money, this lack of access drives poor peasants to informal creditors, such as exploitative local moneylenders, landowners, shopkeepers, and work contractors (jamadars), who capitalize on their desperation to ensnare them in bonded slavery.

Other common features shared by bonded laborers include a lack of education and literacy, which renders them easier to exploit, especially when it comes to keeping track of their debits and credits. Landlessness is another near-universal feature shared by bonded laborers. Without land, individuals have no security or means to cultivate basic food for consumption. As a result, they often mortgage their labor simply to secure shelter and food, and the threat of eviction is often used to ensnare them in severely exploitative labor conditions. Bonded laborers are almost always socially isolated, and they tend to be located a great distance from markets, which renders them reliant on lender-slaveowners to monetize the output of their labor (agricultural products, bricks, carpets, etc.), and these lenders do so inequitably in order to extend the bondage.

Finally, the most important quality aside from poverty and minority ethnicity shared by each and every bonded laborer I met is a lack of any reasonable alternative. The power of this force should not be underestimated, as it is the absence of alternative sources of income, credit, shelter, food, water, and basic security that drives each and every bonded laborer I met to enter into a debt bondage agreement with an exploiter.

The lack of reasonable alternative also provides immense bargaining power to the lender; he can all but dictate the terms of credit, wages, and employment and manipulate the contracts at will, because the destitute laborer has no other option that would empower him to bargain for better terms or walk away. I believe this essential duress negates any argument that the bonded laborer is entering into the agreement voluntarily, which some have suggested as a reason that bonded labor is not a form of slavery.

On the contrary, it is a well-established tenet of contract law that duress to person (physical threats), duress to goods (the threat to seize or damage the contracting party’s property or, in the case of a bonded laborer, to evict him), and economic duress (forces of economic compulsion without a reasonable alternative to the original agreement or renegotiations) render the agreement voidable. Consent is vitiated in the presence of any of these forms of duress, and in almost all cases of bonded labor that I have documented, one if not all of these forms of duress was present at the time of the supposed agreement. Accordingly, few if any of these agreements can be construed as voluntarily entered.

There are other qualities shared by many of the bonded labourers I have documented—such as an inability to diversify household occupations (which would help attenuate the lack of income when one sector is depressed or out of season), a propensity to migrate for income opportunity (migrants are inherently more isolated and vulnerable to exploitation), a sense of fatalism that bondage is the only life available to them, and the tendency of male heads of household to abuse alcohol or abuse their family members.

Slavery In Pakistan

The Global Slavery Index estimates there are 3.1 million people trapped in slavery in the region of Pakistan and among them is a high number of women and children, especially from the minority segments of the society.

The money they owe keeps increasing, spiralling out of reach, thus keeping them and future generations in debt. Reasons for this can include high interest on the amount borrowed, low wages further cut due to corrupt officials, increasing and unlawful deductions, and forged entries into the books that the workers do not get to see.

“The bricks that these workers make are used to make houses, hospitals, schools, universities and the parliament. But they never get to benefit from what they are making”

These people are shelterless and deprived of every facility that those institutes offer: They get no education or health facilities and the system is failing them miserably.

“It seems that these bricks get their red colour from the blood of the bonded labour.”

In Pakistan, it is illegal to employ someone who is under 16 years of age. But almost 70 percent of bonded labourers in Pakistan are children, who make up over one-third of the four million or so people working at brick kilns in Pakistan. Often, they work all day and are denied education.

There are cases where children inherit debts from parents and became bonded as individuals for a long time. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan reports a high mortality rate among children working at brick kilns. In addition, about one in 20 families living in brick kilns have children who have lost their eyesight.

Children are kept as hostages in the event of the parents leaving the kiln, even for a short period. The workers do not sign a contract when they are taken to a brick kiln. Most of them cannot read, so they have no way of finding out what is being added to their accounts.

Some of the workers who manage to flee or are freed are taken back to the kiln by the owners by force. With no inspection of these sites, they have no protection and often end up in harsher conditions upon their return, with a hefty fine added to their existing debt.

There have also been cases where an escaped worker’s daughter has been forcibly married off – or sold – as “payment” for the days he had been in hiding for. As debts are manipulated upwards year after year, an overall sense of helplessness overcomes most labourers, While some may have family members forcibly sold to repay their debts, others give up and commit suicide.

You are encouraged to donate to this project without your support we have not reached this far.